Chapter 34: We are Invited to an Awajun Tribal Village

AS TOLD BY JOHN AGERSTEN

The invitation

We had not been in Tigre Playa very long when a group of Awajun natives arrived to see us. They lived along the Potro River, a tributary that started in the mountains further south and flowed into the Marañon a few kilometers upriver from us. They had heard that we had medications and could help the sick people they had brought with them. During their stay with us, we treated their sick and the group attended the services and heard the gospel. The men could speak some Spanish that they had learned from traveling Spanish-speaking traders and loggers that would come to their area.

After a couple of weeks with us, they returned home. A little over a week later, a group of men from their village returned to Tigre Playa and solemnly handed us a letter with an invitation to come to their village and teach them from the Bible. The letter was written and signed by the teacher and leader of the village. In addition, the paper was covered in fingerprints on both sides and under the fingerprints, the teacher had written the name of the person it belonged to. We were told they were the fingerprints of the leaders and fathers of the village. It had taken them a day and a half by canoe downstream to reach us, and it would take them at least three days rowing upstream to return home just to deliver this invitation. It was a very moving moment!

During this time there were about 20,000 Awajun spread out over a large area, primarily in the west along the upper Marañon above the Pongo de Manseriche Rapids. There were Wycliffe missionaries living in villages there learning the Awajun language and working on translating the New Testament. They told us that one of these missionaries had visited them and established a small school in their village. An Awajun teacher who had received his teacher training at the Wycliffe base came to teach at the school.

I promised we would visit them, but unfortunately, more time passed than I had hoped before I could make that promise a reality. Over the next few weeks, we visited some of the neighboring villages on the Marañon. At the same time, I started building the house, and in April, we went as a family in the houseboat, “El Sembrador”, to Yurimaguas to get and cash our support checks from Norway. We also needed to do some shopping while we were there, and Gro needed to visit a dentist to take care of an aching tooth. We were only there for three days but accomplished everything we needed to in that time.

We had not been in Tigre Playa very long when a group of Awajun natives arrived to see us. They lived along the Potro River, a tributary that started in the mountains further south and flowed into the Marañon a few kilometers upriver from us. They had heard that we had medications and could help the sick people they had brought with them. During their stay with us, we treated their sick and the group attended the services and heard the gospel. The men could speak some Spanish that they had learned from traveling Spanish-speaking traders and loggers that would come to their area.

After a couple of weeks with us, they returned home. A little over a week later, a group of men from their village returned to Tigre Playa and solemnly handed us a letter with an invitation to come to their village and teach them from the Bible. The letter was written and signed by the teacher and leader of the village. In addition, the paper was covered in fingerprints on both sides and under the fingerprints, the teacher had written the name of the person it belonged to. We were told they were the fingerprints of the leaders and fathers of the village. It had taken them a day and a half by canoe downstream to reach us, and it would take them at least three days rowing upstream to return home just to deliver this invitation. It was a very moving moment!

During this time there were about 20,000 Awajun spread out over a large area, primarily in the west along the upper Marañon above the Pongo de Manseriche Rapids. There were Wycliffe missionaries living in villages there learning the Awajun language and working on translating the New Testament. They told us that one of these missionaries had visited them and established a small school in their village. An Awajun teacher who had received his teacher training at the Wycliffe base came to teach at the school.

I promised we would visit them, but unfortunately, more time passed than I had hoped before I could make that promise a reality. Over the next few weeks, we visited some of the neighboring villages on the Marañon. At the same time, I started building the house, and in April, we went as a family in the houseboat, “El Sembrador”, to Yurimaguas to get and cash our support checks from Norway. We also needed to do some shopping while we were there, and Gro needed to visit a dentist to take care of an aching tooth. We were only there for three days but accomplished everything we needed to in that time.

Our first visit to an Awajun village in the Potro River in May 1970

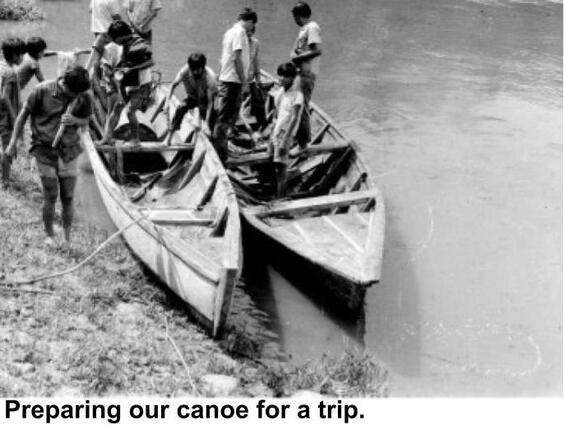

At the beginning of May, I was finally able to make the promised trip to the village Porvenir in Potro. Two of the newly baptized youth from Tigre Playa went with me. It was a strenuous journey up the narrow and winding river in our new canoe. The current is quite calm as the river floats through the flat landscape, but sandbanks and trees that had fallen into the river made navigating it very difficult at times. The jungle was like a wall on both sides of the narrow river. We saw monkeys, capybaras, and an abundance of different kinds of birds. We knew there were turtles and alligators in the river as well, but they were warier and would hide at the sound of our engine.

After about four hours we came to the first inhabited spot on the river. The house was situated at the mouth of a smaller tributary, Achayacu. Here we encountered a mestizo man who declared himself the “patrón” of the Awajun who lived further upriver. “I control them”, he said. He would make them work for him in the woods cutting lumber. Many in the tribe were indebted to him because he would take advantage of their ignorance about pricing, money, and financing. It was easy to trick them into owing him money and practically enslaving them. Unfortunately, over time, we saw many take advantage of the natives in this way throughout the jungle.

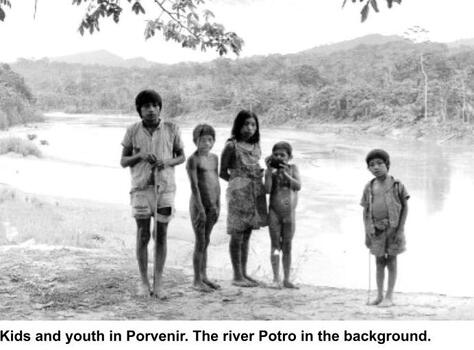

We prepared ourselves a meal over an open fire before continuing upriver. We traveled a further two or three hours before we rounded a big turn and saw the village Porvenir. The people had heard our engine, and a large crowd now waited for us on the high riverbank. The landscape had gotten hillier as we traveled, and the village was situated safe from flooding on high ground. Around the village, we could see small fields of banana and manioc plants. These are staple foods and were eaten at every meal. Game and fish were enjoyed when they could get it, but this was not always available. Evidently chicken and eggs were also part of their diet, as we could see some hens wandering around the village.

At the beginning of May, I was finally able to make the promised trip to the village Porvenir in Potro. Two of the newly baptized youth from Tigre Playa went with me. It was a strenuous journey up the narrow and winding river in our new canoe. The current is quite calm as the river floats through the flat landscape, but sandbanks and trees that had fallen into the river made navigating it very difficult at times. The jungle was like a wall on both sides of the narrow river. We saw monkeys, capybaras, and an abundance of different kinds of birds. We knew there were turtles and alligators in the river as well, but they were warier and would hide at the sound of our engine.

After about four hours we came to the first inhabited spot on the river. The house was situated at the mouth of a smaller tributary, Achayacu. Here we encountered a mestizo man who declared himself the “patrón” of the Awajun who lived further upriver. “I control them”, he said. He would make them work for him in the woods cutting lumber. Many in the tribe were indebted to him because he would take advantage of their ignorance about pricing, money, and financing. It was easy to trick them into owing him money and practically enslaving them. Unfortunately, over time, we saw many take advantage of the natives in this way throughout the jungle.

We prepared ourselves a meal over an open fire before continuing upriver. We traveled a further two or three hours before we rounded a big turn and saw the village Porvenir. The people had heard our engine, and a large crowd now waited for us on the high riverbank. The landscape had gotten hillier as we traveled, and the village was situated safe from flooding on high ground. Around the village, we could see small fields of banana and manioc plants. These are staple foods and were eaten at every meal. Game and fish were enjoyed when they could get it, but this was not always available. Evidently chicken and eggs were also part of their diet, as we could see some hens wandering around the village.

Accommodations for the night, the first service, and vampire bats.

We received a warm welcome from the village leader, “El Apu” and the teacher. They helped us carry our luggage to an empty bamboo hut that was a little set apart from the rest of the houses. The only “furniture” in the hut was a couple of wooden stumps. I was glad I had brought my hammock to sit in. It was already getting late, so we started to set up our bedding and mosquito nets right away. I had brought my air mattress and had an interested audience watching as I pumped it up with the foot pump. This was new to them and very entertaining. The two young men with me set up as they were used to with just a sheet on the bamboo floor. They had to share a mosquito net as one of them had forgotten his at home.

They wanted to hold a service right away, so I fired up the paraffin lamp I had brought with me. We were to meet in the schoolhouse. The house was completely full and people were all talking at once. It seemed they were very excited about our arrival. As we entered, it quieted down, and the teacher welcomed everyone to the service. He served as our translator to Awajun as we gave our testimonies. We also taught them a couple of choruses in Spanish before we closed the service. After the service, we were served boiled bananas, manioc, and eggs. With few exceptions, this was the menu throughout the week we stayed in Potro.

During the night, one of the young men ended up with his elbow sticking out of their shared mosquito net and was bitten by a vampire bat. The next morning, I discovered some blood on the floor by his arm. The vampire bat injects an anticoagulation agent into the wound when it bites. The wound was not severe: most likely he had moved his arm and scared the bat away. I cleaned the bite and the surrounding skin, and it healed nicely. We were told that bat bites happened quite often in the village. Most slept without nets as there were not so many mosquitoes in this area. They just wrapped themselves up in a piece of cloth on a bark mat on the floor.

We received a warm welcome from the village leader, “El Apu” and the teacher. They helped us carry our luggage to an empty bamboo hut that was a little set apart from the rest of the houses. The only “furniture” in the hut was a couple of wooden stumps. I was glad I had brought my hammock to sit in. It was already getting late, so we started to set up our bedding and mosquito nets right away. I had brought my air mattress and had an interested audience watching as I pumped it up with the foot pump. This was new to them and very entertaining. The two young men with me set up as they were used to with just a sheet on the bamboo floor. They had to share a mosquito net as one of them had forgotten his at home.

They wanted to hold a service right away, so I fired up the paraffin lamp I had brought with me. We were to meet in the schoolhouse. The house was completely full and people were all talking at once. It seemed they were very excited about our arrival. As we entered, it quieted down, and the teacher welcomed everyone to the service. He served as our translator to Awajun as we gave our testimonies. We also taught them a couple of choruses in Spanish before we closed the service. After the service, we were served boiled bananas, manioc, and eggs. With few exceptions, this was the menu throughout the week we stayed in Potro.

During the night, one of the young men ended up with his elbow sticking out of their shared mosquito net and was bitten by a vampire bat. The next morning, I discovered some blood on the floor by his arm. The vampire bat injects an anticoagulation agent into the wound when it bites. The wound was not severe: most likely he had moved his arm and scared the bat away. I cleaned the bite and the surrounding skin, and it healed nicely. We were told that bat bites happened quite often in the village. Most slept without nets as there were not so many mosquitoes in this area. They just wrapped themselves up in a piece of cloth on a bark mat on the floor.

Bible studies and services in Porvenir

During the week of our stay, we held services and had conversations with people, where we taught them in simple ways the foundational truths of the Gospel. We also prayed with those who requested it. Sunday, after preaching, I asked if anyone wanted to receive salvation through Jesus Christ. To my surprise, nearly everyone came forward! About fifty people, both young and old, gathered in front of the table we were using as a pulpit. I thought they must not have understood what I was asking, or that maybe the translation had not truly expressed what I meant, so I asked them to go and sit back down. I explained again in more detail what it meant to accept salvation and dedicate one’s life to Christ. I gave the invitation again. The same group came forward again and a few more that had not done so the first time. It was quite an experience to pray with them. They prayed loudly and with great fervor, and quite some time passed before we finally concluded the service with some choruses. The teacher told us afterward that they had been praying for forgiveness for all their sins, including murders, fights, adultery, and many other things. The Holy Spirit had truly softened their hard hearts. One of the ones that came forward was a twelve-year-old boy, Gustavo Sanchez. He would later be used mightily by the Lord to establish many groups of believers among the Awajun villages in this area.

An older man came and wanted to talk to me just before we left. He told me he had a problem. He had four wives and now felt that this may not be right as a believer. I knew polygamy was very common among the natives as this was both a symbol of status and extra hands to help in the fields. However, I did not address the issue during my stay. He wanted my opinion and advice on what to do about it. I told him I did not have a simple answer in this particular situation; he would need to pray and ask the Lord for wisdom. With time it became more usual among the natives to only have one wife, so it became less of an issue.

During the week of our stay, we held services and had conversations with people, where we taught them in simple ways the foundational truths of the Gospel. We also prayed with those who requested it. Sunday, after preaching, I asked if anyone wanted to receive salvation through Jesus Christ. To my surprise, nearly everyone came forward! About fifty people, both young and old, gathered in front of the table we were using as a pulpit. I thought they must not have understood what I was asking, or that maybe the translation had not truly expressed what I meant, so I asked them to go and sit back down. I explained again in more detail what it meant to accept salvation and dedicate one’s life to Christ. I gave the invitation again. The same group came forward again and a few more that had not done so the first time. It was quite an experience to pray with them. They prayed loudly and with great fervor, and quite some time passed before we finally concluded the service with some choruses. The teacher told us afterward that they had been praying for forgiveness for all their sins, including murders, fights, adultery, and many other things. The Holy Spirit had truly softened their hard hearts. One of the ones that came forward was a twelve-year-old boy, Gustavo Sanchez. He would later be used mightily by the Lord to establish many groups of believers among the Awajun villages in this area.

An older man came and wanted to talk to me just before we left. He told me he had a problem. He had four wives and now felt that this may not be right as a believer. I knew polygamy was very common among the natives as this was both a symbol of status and extra hands to help in the fields. However, I did not address the issue during my stay. He wanted my opinion and advice on what to do about it. I told him I did not have a simple answer in this particular situation; he would need to pray and ask the Lord for wisdom. With time it became more usual among the natives to only have one wife, so it became less of an issue.

A second visit at the end of May

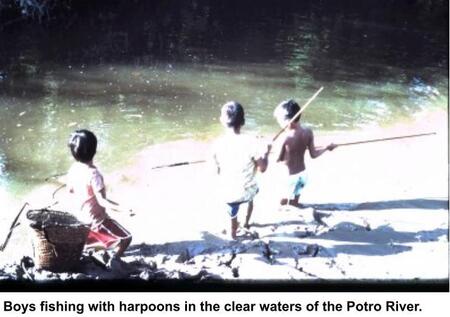

Just three weeks later, at the end of May, I traveled up Potro to visit the village of Porvenir again with my two young helpers. I was anxious to see how the new believers were doing. We knew that the Shaman who lived a little further into the woods from the village, held great power over the natives in the area. Many families still lived in an isolated clearing in the jungle where they built their huts and had their small vegetable fields. The men would help with clearing a field every three or four years, but it was the women and children who planted and worked the plot. The men would hunt and fish.

Most girls were promised in marriage by the time they were 8 - 9 years old, and were usually married by the age of 14. It was a hard life. Unfortunately, drunkenness was also a problem, especially around parties and festivals. What they indulged in was the masato, a drink made from manioc. After fermenting for a few days, the alcohol levels in the drink could be quite high. When it is fresh, it is not fermented yet and is an important part of the household diet. It is the first thing offered to guests. It would be considered impolite to refuse; you had to at least take a sip out of the bowl as it was passed around. It didn’t taste bad, especially if you could keep from thinking about that part of the preparation involved someone chewing it and spitting it back in the pot.

We were only staying three days this time, but they were full of services, Bible studies, and conversations. It was quite a diverse congregation. Boys without a stitch of clothing would occupy the front row on one side. They sang in full voice and with much excitement. Behind them were the men with tattooed faces and long hair, and many of the older men preferred their traditional skirt-like wraps to pants. The women and girls sat on the other side. Most of them had lots of adornments hanging around their necks, arms, and ankles. They wore a long piece of cloth that was tied over one shoulder and used a small cloth to swat at insects to keep them away from themselves and the babies they carried on their hips. Again, many came forward for prayer, even those who had come forward last time. They cried and prayed loudly without inhibition or concern about someone hearing them. It seemed like this openness was part of their culture.

A balsa raft loaded with sand

On the way up the river, we had noticed some large sand banks. I was eager to continue with our house in Tigre Playa and we needed sand to mix the concrete. Some of the men in the village helped us build a large raft out of balsa wood. We then loaded it with as much sand as it could handle and tied the raft to our boat where we could push it in front of us. In trade for the help, the men were happy to receive fishing hooks, string, and other small tools useful in the jungle. It was hard work going downriver with the raft. There were so many twists and turns and we had to try to keep the raft in the middle of the narrow river so it wouldn’t get stuck on trees and branches that had fallen along the riverbanks. It was easier once we came out in the bigger Marañon River. Turning it in toward land as we arrived in Tigre Playa, however, turned out to be quite a challenge. The strong current wanted to pull it back into the middle of the river, but with much effort, we finally got it where we wanted it. We had good help in unloading the sand, and now I could finally continue working on the foundation wall. It had been standing half-finished for a while due to the flooding we had experienced and due to the lack of sand.

Over the next few months, we were busy with the house, helping the sick, and the work in the church in Tigre Playa, so we did not have an opportunity to return to Potro the rest of that year. We did, however, have several visits from them, usually when they brought someone sick or injured. They were always eager to attend the services, even though many of them did not understand much Spanish.

Just three weeks later, at the end of May, I traveled up Potro to visit the village of Porvenir again with my two young helpers. I was anxious to see how the new believers were doing. We knew that the Shaman who lived a little further into the woods from the village, held great power over the natives in the area. Many families still lived in an isolated clearing in the jungle where they built their huts and had their small vegetable fields. The men would help with clearing a field every three or four years, but it was the women and children who planted and worked the plot. The men would hunt and fish.

Most girls were promised in marriage by the time they were 8 - 9 years old, and were usually married by the age of 14. It was a hard life. Unfortunately, drunkenness was also a problem, especially around parties and festivals. What they indulged in was the masato, a drink made from manioc. After fermenting for a few days, the alcohol levels in the drink could be quite high. When it is fresh, it is not fermented yet and is an important part of the household diet. It is the first thing offered to guests. It would be considered impolite to refuse; you had to at least take a sip out of the bowl as it was passed around. It didn’t taste bad, especially if you could keep from thinking about that part of the preparation involved someone chewing it and spitting it back in the pot.

We were only staying three days this time, but they were full of services, Bible studies, and conversations. It was quite a diverse congregation. Boys without a stitch of clothing would occupy the front row on one side. They sang in full voice and with much excitement. Behind them were the men with tattooed faces and long hair, and many of the older men preferred their traditional skirt-like wraps to pants. The women and girls sat on the other side. Most of them had lots of adornments hanging around their necks, arms, and ankles. They wore a long piece of cloth that was tied over one shoulder and used a small cloth to swat at insects to keep them away from themselves and the babies they carried on their hips. Again, many came forward for prayer, even those who had come forward last time. They cried and prayed loudly without inhibition or concern about someone hearing them. It seemed like this openness was part of their culture.

A balsa raft loaded with sand

On the way up the river, we had noticed some large sand banks. I was eager to continue with our house in Tigre Playa and we needed sand to mix the concrete. Some of the men in the village helped us build a large raft out of balsa wood. We then loaded it with as much sand as it could handle and tied the raft to our boat where we could push it in front of us. In trade for the help, the men were happy to receive fishing hooks, string, and other small tools useful in the jungle. It was hard work going downriver with the raft. There were so many twists and turns and we had to try to keep the raft in the middle of the narrow river so it wouldn’t get stuck on trees and branches that had fallen along the riverbanks. It was easier once we came out in the bigger Marañon River. Turning it in toward land as we arrived in Tigre Playa, however, turned out to be quite a challenge. The strong current wanted to pull it back into the middle of the river, but with much effort, we finally got it where we wanted it. We had good help in unloading the sand, and now I could finally continue working on the foundation wall. It had been standing half-finished for a while due to the flooding we had experienced and due to the lack of sand.

Over the next few months, we were busy with the house, helping the sick, and the work in the church in Tigre Playa, so we did not have an opportunity to return to Potro the rest of that year. We did, however, have several visits from them, usually when they brought someone sick or injured. They were always eager to attend the services, even though many of them did not understand much Spanish.

The return to Potro in February 1971

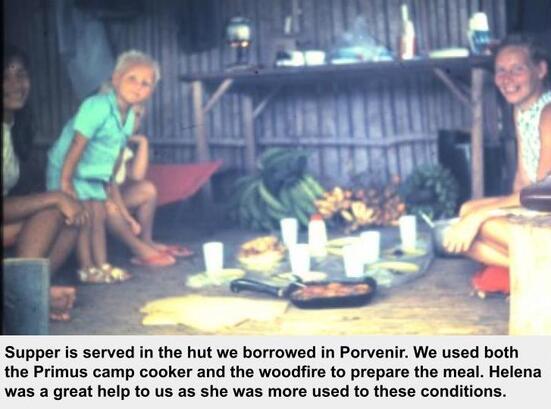

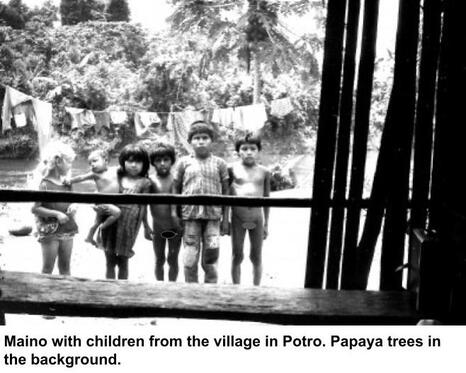

In February 1971, several months after the first two visits, we prepared to travel to Potro again. This time, the whole family would go. Cesar, one of the young men I had gone with last time, Edith, the Norwegian missionary who had arrived in December, and Helena, our house help, would also accompany us. Gro had long wished to visit the Awajun in Porvenir, and finally, she would get to go with me. Besides the camping beds, air mattresses, bedding, and mosquito netting, we also took with us the paraffin lamp and the Primus camp cooker. Of course, we also needed flashlights, matches, some toiletries, and changes of clothing. We decided to bring a few cans and dry goods to add to the offered menu, particularly with thought for Maino and Lewi. It was a fully loaded boat that left Tigre Playa one early February morning.

After returning safely home from that trip, Gro wrote in a letter home: “It was a very interesting trip and full of rich experiences. Many came to the Bible studies and the services. Some came for the first time from huts further into the jungle. They also wanted us to pray for them and to receive Jesus. With the help of a translator, I was able to talk to some of the women. They had many problems and challenges that I could not relate to. A couple of them told me they fought a lot with their husband’s other wives; others told me they felt very jealous when their husbands brought home a younger wife. Almost all of them related their sorrow over the death of some of their children. They told me the children died because the shaman had cursed them, or because spirits in the jungle had bewitched them.”

In February 1971, several months after the first two visits, we prepared to travel to Potro again. This time, the whole family would go. Cesar, one of the young men I had gone with last time, Edith, the Norwegian missionary who had arrived in December, and Helena, our house help, would also accompany us. Gro had long wished to visit the Awajun in Porvenir, and finally, she would get to go with me. Besides the camping beds, air mattresses, bedding, and mosquito netting, we also took with us the paraffin lamp and the Primus camp cooker. Of course, we also needed flashlights, matches, some toiletries, and changes of clothing. We decided to bring a few cans and dry goods to add to the offered menu, particularly with thought for Maino and Lewi. It was a fully loaded boat that left Tigre Playa one early February morning.

After returning safely home from that trip, Gro wrote in a letter home: “It was a very interesting trip and full of rich experiences. Many came to the Bible studies and the services. Some came for the first time from huts further into the jungle. They also wanted us to pray for them and to receive Jesus. With the help of a translator, I was able to talk to some of the women. They had many problems and challenges that I could not relate to. A couple of them told me they fought a lot with their husband’s other wives; others told me they felt very jealous when their husbands brought home a younger wife. Almost all of them related their sorrow over the death of some of their children. They told me the children died because the shaman had cursed them, or because spirits in the jungle had bewitched them.”

These were very common ways of explaining sicknesses both among the tribes and the mestizos along the Marañon River. We had heard this a lot during our year in Tigre Playa as people came to us for treatment and medications.

Gro continues in her letter: “After a few days in Porvenir, we needed to head back to Tigre Playa. On the way downriver, the engine failed. We could not get it started again. John and Cesar had to row for almost two hours before we finally reached Tigre Playa. Fortunately, we were traveling downriver; rowing against the current would have been almost impossible with our fully loaded boat. Once home, John took the engine completely apart, found the fault, and got it running again. This is a relief, as we are planning a trip up the Morona in just a couple of days to visit both Chapra and mestizo villages.”

This would be our last trip to Potro during our first period in Peru, but we went many times in the following years. The population has increased and now there are more villages along Potro and its tributaries.

Gro continues in her letter: “After a few days in Porvenir, we needed to head back to Tigre Playa. On the way downriver, the engine failed. We could not get it started again. John and Cesar had to row for almost two hours before we finally reached Tigre Playa. Fortunately, we were traveling downriver; rowing against the current would have been almost impossible with our fully loaded boat. Once home, John took the engine completely apart, found the fault, and got it running again. This is a relief, as we are planning a trip up the Morona in just a couple of days to visit both Chapra and mestizo villages.”

This would be our last trip to Potro during our first period in Peru, but we went many times in the following years. The population has increased and now there are more villages along Potro and its tributaries.