Chapter 28: The First Mission Trip in El Sembrador

AS TOLD BY JOHNAGERSTEN

Leaving Borja for the mouth of Morona.

We enjoyed our time in Borja. We held some services and made friends during the week we were there, and several people asked us to settle in the village. We felt like we needed to continue our travels to get more familiar with the area, but assured them that we would be back here sometime to share more about the Gospel.

On Sunday, October 26th, 1969, we took farewell with the friends that had gathered at the river’s edge to see us off. We headed east down the river Marañon and we were moving pretty fast. Here the river was broader than above the Manseriche rapids, but the current was still strong, and there were plenty of rocky banks and floating logs to make maneuvering quite exciting for river novices like us.

As mentioned before, one person would steer from the front of the boat, and another would have to control the outboard motor in the back. The motorist could not see ahead from the back, so we created a signal system to be able to communicate with each other. Whoever was steering at the front used the sounds of an alarm clock to signal to the motorist different commands such as “full speed”,” slow”, “stop”, and “start”. This worked well.

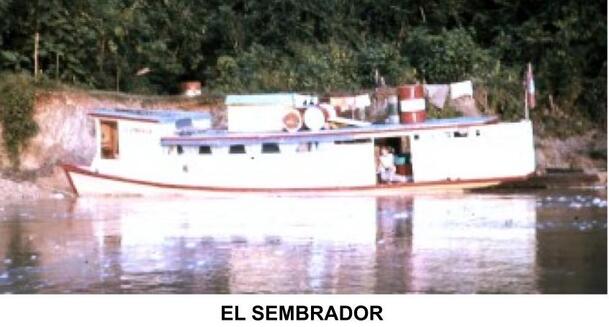

We were pretty loaded down as we left Borja. The boat was divided into three main parts: the small wheelhouse in the front, our living area in the middle, and a storage room in the back. Gro and I slept on the benches along the sides of the middle of the living area, and I had built two small beds with raised sides for Maino and Lewi in the back of the room. Our dining room table from Norway fit snugly between the benches. There was barely room to get by as we moved toward the front or the back of the boat. The small kitchen counter and the stove and fridge we had brought from Bagua stood at the front end of the living area. Everything was nailed down and fastened securely. Our Petrolux paraffin lamp provided good lighting but unfortunately also unwanted heat. The storage room was full of supplies. We knew there would be no gas stations or stores where we were traveling, so we had prepared well for the long trip. We carried with us five barrels of gas, one barrel of paraffin, and sacks of rice, flour and beans. We also brought boxes with canned goods. Some of these things were stored under the benches in the living area. Gro was already used to baking bread, and we were counting on being able to buy fruits, vegetables, and meats like chicken, fish, and wild animals in the villages we visited.

The first night in El Sembrador

We didn’t leave Borja till late morning, so we did not reach the mouth of Morona that first day. Late afternoon, we realized we would have to find a place to dock and cook supper before it got dark. We found a place in a bend where the current was calmer and tied the boat to a tree. The sun goes down around 6 - 6:30 pm year-round, and it gets dark quickly. We had barely eaten when darkness descended and the mosquitos suddenly invaded the boat! We had mosquito netting in the windows, but the mosquitos poured in through any cracks they found.

I had experienced a lot of mosquitos on my previous trip on the Morona, and we had been warned in Borja that there was a lot along the Marañon river as well. Because of this, we had purchased a thin fabric that can be sewn into mosquito nets to hang over a bed. We had a sewing machine with us that could be used both with or without electricity. We had set it up in the wheelhouse across from where the motorist was going to sleep. So now we lathered on the mosquito repellent, and Gro sat down at the machine to the light of the paraffin lamp and made mosquito netting for all of us in record time while the mosquitos buzzed around us. She finished the children’s nets first, and finally, ours were ready to hang up as well. It was late by now, and we were tired from an eventful and exciting day. It felt good to escape the mosquitos and relax on the bed under the net. Although the bed was just a wooden bench with a thin foam mattress, we all fell asleep quickly to the sounds in the jungle and the gravel being rolled around by the current under the boat.

I felt like I had just fallen asleep when I was awakened by the sun shining in through the windows the next morning. The mosquitos had retreated back into the jungle, and we were able to eat our breakfast peacefully before continuing our trip down the river. It was getting broader and calmer, and the rock was giving way to sand and mud banks on the inner bends. It did not take us long to reach the mouth of the Morona river.

However, we were not able to dock at the village there yet. We had been told that we needed to report to the military post in Barranca, further down the Marañon river. There we would have to obtain permission to travel in the area. This whole area was under military control due to a border dispute with Ecuador. When we reached Barranca, the commander asked us several questions, looked at our documents, and gave us the travel permit with no problem. On the way upriver back to Morona, we noticed several small villages that we decided we wanted to visit later.

We enjoyed our time in Borja. We held some services and made friends during the week we were there, and several people asked us to settle in the village. We felt like we needed to continue our travels to get more familiar with the area, but assured them that we would be back here sometime to share more about the Gospel.

On Sunday, October 26th, 1969, we took farewell with the friends that had gathered at the river’s edge to see us off. We headed east down the river Marañon and we were moving pretty fast. Here the river was broader than above the Manseriche rapids, but the current was still strong, and there were plenty of rocky banks and floating logs to make maneuvering quite exciting for river novices like us.

As mentioned before, one person would steer from the front of the boat, and another would have to control the outboard motor in the back. The motorist could not see ahead from the back, so we created a signal system to be able to communicate with each other. Whoever was steering at the front used the sounds of an alarm clock to signal to the motorist different commands such as “full speed”,” slow”, “stop”, and “start”. This worked well.

We were pretty loaded down as we left Borja. The boat was divided into three main parts: the small wheelhouse in the front, our living area in the middle, and a storage room in the back. Gro and I slept on the benches along the sides of the middle of the living area, and I had built two small beds with raised sides for Maino and Lewi in the back of the room. Our dining room table from Norway fit snugly between the benches. There was barely room to get by as we moved toward the front or the back of the boat. The small kitchen counter and the stove and fridge we had brought from Bagua stood at the front end of the living area. Everything was nailed down and fastened securely. Our Petrolux paraffin lamp provided good lighting but unfortunately also unwanted heat. The storage room was full of supplies. We knew there would be no gas stations or stores where we were traveling, so we had prepared well for the long trip. We carried with us five barrels of gas, one barrel of paraffin, and sacks of rice, flour and beans. We also brought boxes with canned goods. Some of these things were stored under the benches in the living area. Gro was already used to baking bread, and we were counting on being able to buy fruits, vegetables, and meats like chicken, fish, and wild animals in the villages we visited.

The first night in El Sembrador

We didn’t leave Borja till late morning, so we did not reach the mouth of Morona that first day. Late afternoon, we realized we would have to find a place to dock and cook supper before it got dark. We found a place in a bend where the current was calmer and tied the boat to a tree. The sun goes down around 6 - 6:30 pm year-round, and it gets dark quickly. We had barely eaten when darkness descended and the mosquitos suddenly invaded the boat! We had mosquito netting in the windows, but the mosquitos poured in through any cracks they found.

I had experienced a lot of mosquitos on my previous trip on the Morona, and we had been warned in Borja that there was a lot along the Marañon river as well. Because of this, we had purchased a thin fabric that can be sewn into mosquito nets to hang over a bed. We had a sewing machine with us that could be used both with or without electricity. We had set it up in the wheelhouse across from where the motorist was going to sleep. So now we lathered on the mosquito repellent, and Gro sat down at the machine to the light of the paraffin lamp and made mosquito netting for all of us in record time while the mosquitos buzzed around us. She finished the children’s nets first, and finally, ours were ready to hang up as well. It was late by now, and we were tired from an eventful and exciting day. It felt good to escape the mosquitos and relax on the bed under the net. Although the bed was just a wooden bench with a thin foam mattress, we all fell asleep quickly to the sounds in the jungle and the gravel being rolled around by the current under the boat.

I felt like I had just fallen asleep when I was awakened by the sun shining in through the windows the next morning. The mosquitos had retreated back into the jungle, and we were able to eat our breakfast peacefully before continuing our trip down the river. It was getting broader and calmer, and the rock was giving way to sand and mud banks on the inner bends. It did not take us long to reach the mouth of the Morona river.

However, we were not able to dock at the village there yet. We had been told that we needed to report to the military post in Barranca, further down the Marañon river. There we would have to obtain permission to travel in the area. This whole area was under military control due to a border dispute with Ecuador. When we reached Barranca, the commander asked us several questions, looked at our documents, and gave us the travel permit with no problem. On the way upriver back to Morona, we noticed several small villages that we decided we wanted to visit later.

Puerto America

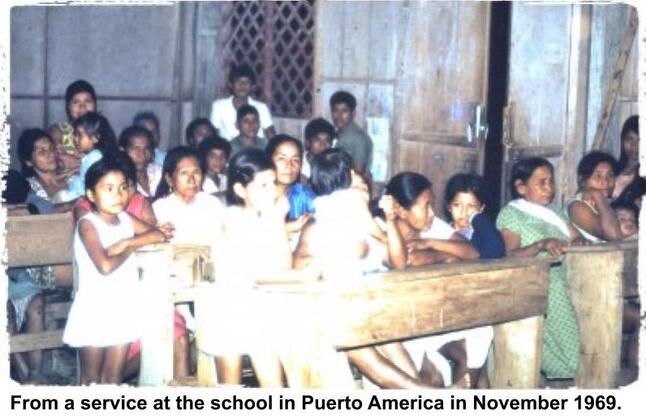

We arrived back at the mouth of the Morona river late that afternoon. As soon as we turned into its clear waters, we could see the village of Puerto America. We docked, then went up on the riverbank. Soon several curious children gathered around us. I started playing the accordion, and that brought many people wanting to see what was going on. After singing a few songs, we started to chat with several people. Everyone was curious about this family of white people visiting their village. Some recognized me from my earlier trip when I had traveled through here on the merchant’s boat. We were invited to hold services both at the school and at the house of the patrón. Many people in the village worked for the patrón and he considered himself the boss in the village. He had a big house and owned all the cattle we could see behind the houses.

We stayed in Puerto America for a few days. It was the largest village in the Morona region, and the regional government office was located there. Most of the houses were built on stilts with palm tree walls and palm-leaf roofs. Only the school and the regional office had tin roofs. We got to know the mayor, and he gave us a lot of information about Morona and its inhabitants. He told us we could reach the Ecuadorian border in five days with our boat by traveling directly upriver. The first couple of days of traveling would take us to small villages inhabited primarily by Spanish-speaking mestizos. After that, we would enter the tribal areas, first to the Chapra tribe, then the Wampis, and finally, the Achuar tribe who lived closest to the border of Ecuador. Many of the tribal people also lived along the tributaries to the Morona.

We visited all the homes in Puerto America, talked to people, and gave tracts and Bible portions to those who could read. There had been an elementary school there for several years, so many were literate. We also invited them to a service each evening, and many came to hear the gospel of Jesus Christ. The children quickly learned some of the choruses we sang, and we could hear them singing in the village in the afternoon after school. We held some services in the open air as well, and one day the people started laughing. I soon learned the cause of their merriment; a dog had raised a leg and proceeded to wet a corner of my accordion! The dog was shooed away, and the service could proceed without further interruption. We know that the seed of God’s Word that was sown during that first visit has borne fruit. Among others, some of the children that heard the Gospel at that time are now actively engaged in churches both here and in other villages.

Visiting other villages on Morona’s lower course.

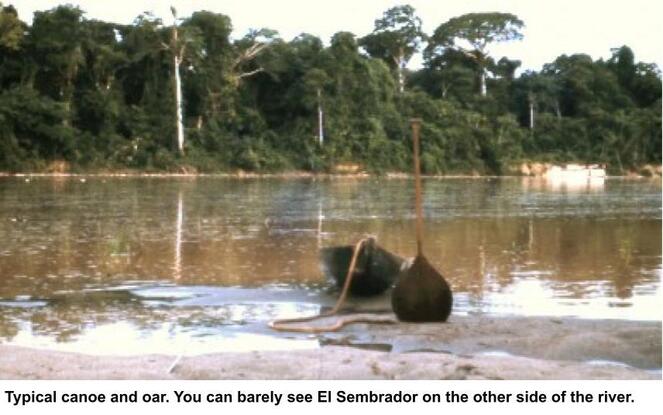

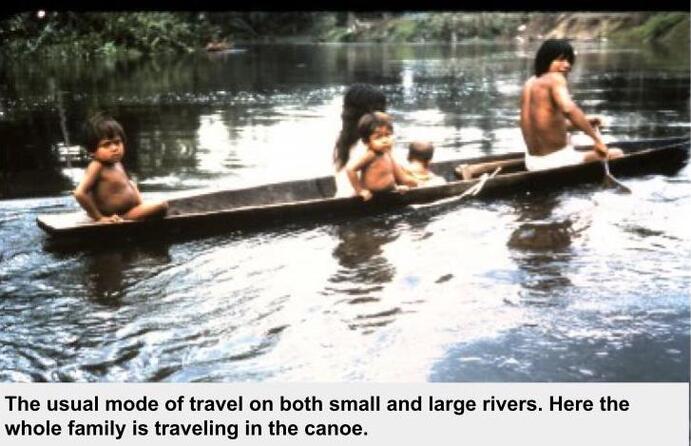

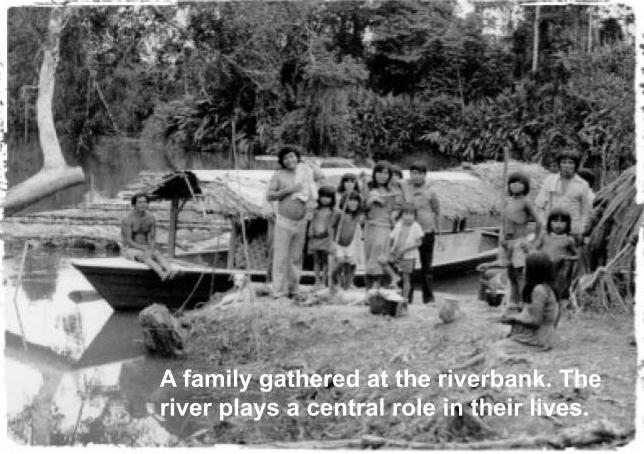

Soon, we felt we had to continue up the Morona. The river was calm here as it flowed through bend after bend. Sometimes it felt like we were traveling in circles. We would dock by most of the houses and small villages we passed. In some places, there was just a single house in a clearing by the river. Here a family would live alone in a simple bamboo hut surrounded by banana plants and small fields with manioc, sweet potatoes, and maybe a few beans. Usually, they had a few chickens, and maybe a pig or two. Hunting and fishing were part of their daily life. Most families owned a rifle for hunting. In this way, they were self-sufficient as far as food. The closest neighbor may live two-three hours away by canoe.

For the most part, we saw small villages with three or more houses. If it had more than ten houses, it was considered a large village. As we would dock we were sometimes asked first if we sold liquor. The merchants that traveled the rivers often opened their sales by selling this. Some wondered if we sold seeds because the name of our boat, El Sembrador, was painted on the side. That created a nice opening to tell about the Seed, the Word of God. Many heard God’s Word for the first time during this trip. Those who could read eagerly received the tracts and portions of the Bible that we had with us. We were also able to sell complete Bibles and New Testaments at subsidized prices. In fact, most of the time we traded them for some fish, or a chicken since few of them had any cash. This worked out for us since we needed the food.

Soon, we felt we had to continue up the Morona. The river was calm here as it flowed through bend after bend. Sometimes it felt like we were traveling in circles. We would dock by most of the houses and small villages we passed. In some places, there was just a single house in a clearing by the river. Here a family would live alone in a simple bamboo hut surrounded by banana plants and small fields with manioc, sweet potatoes, and maybe a few beans. Usually, they had a few chickens, and maybe a pig or two. Hunting and fishing were part of their daily life. Most families owned a rifle for hunting. In this way, they were self-sufficient as far as food. The closest neighbor may live two-three hours away by canoe.

For the most part, we saw small villages with three or more houses. If it had more than ten houses, it was considered a large village. As we would dock we were sometimes asked first if we sold liquor. The merchants that traveled the rivers often opened their sales by selling this. Some wondered if we sold seeds because the name of our boat, El Sembrador, was painted on the side. That created a nice opening to tell about the Seed, the Word of God. Many heard God’s Word for the first time during this trip. Those who could read eagerly received the tracts and portions of the Bible that we had with us. We were also able to sell complete Bibles and New Testaments at subsidized prices. In fact, most of the time we traded them for some fish, or a chicken since few of them had any cash. This worked out for us since we needed the food.

Copal

We stopped for a couple of nights in Copal. It was a larger village situated at the mouth of a tributary with the same name. There was a patrón in this village like in Puerto America. Most of the patróns had cattle, a larger house, a boat with a motor, a small store, and several people that worked for them. Some also dealt in lumber. When the water levels rose, they would float the lumber down the small streams to Morona, and a tug boat would come from Iquitos and pull it further down the Marañon and into the Amazon where it would be sold. There was good money to be made in this business, especially since the patróns generally paid their workers a pittance. Many of them were basically slaves to him. The goods in the stores were expensive compared to the workers salaries, and then they ended up in debt to the patrón so they had to keep working for him. It didn’t help that one of the more popular wares was liquor. We were saddened to see this vicious circle of poverty and exploitation. Fortunately, this system has lessened over the years as people have become more educated.

The patrón in Copal was very excited that we had come. He was preparing for a large celebration of a Catholic holiday and invited us to the party. There was not a church in Copal, but the inhabitants knew of the Catholic holidays, and it was a good opportunity for the whole village to party with plenty of food and alcohol. There were not really any religious aspects to this celebration other than the name. The patrón had sent his workers hunting for many days and showed us a lot of smoked meat from wild boar and many live turtles of both the water and land varieties. They had also prepared many jugs of “Masato”, a drink made from manioc. The boiled manioc is mashed, then chewed, and spit back in the pot. This starts the fermentation process. When it is fresh, it is not fermented yet, and it is used as a drink even for children. However, when it has been stored for several days, it becomes very strong. These jugs had been set aside 3 - 5 days ago and were quite alcoholic by this point. According to the patrón, everything was in place for a great party.

We declined the invitation as politely as we could, but since the party was not to be held until the following evening, we asked him if we could hold a service in his house this evening. He heartily agreed and sent messengers out to the village to spread the news about the meeting. Back in our boat, we had time to eat dinner and prepare for the service before we headed back up to the patrón’s big house. As darkness fell, people arrived for the meeting. To our surprise, 50 - 60 people showed up. Where did they all come from? All we had seen were a few houses! But we soon discovered that many lived further in the jungle next to small lakes or creeks, and their houses could not be seen from the river. It was the first time for most of them to hear the good news of salvation through Jesus Christ. Everyone enjoyed the accordion and the singing, and the children and the younger people soon joined in as they learned the choruses. One of the patrón’s adult sons asked for prayer. We had a good talk with him and prayed with him after most people had gone home. He was the first one on this trip we were able to pray for.

We stopped for a couple of nights in Copal. It was a larger village situated at the mouth of a tributary with the same name. There was a patrón in this village like in Puerto America. Most of the patróns had cattle, a larger house, a boat with a motor, a small store, and several people that worked for them. Some also dealt in lumber. When the water levels rose, they would float the lumber down the small streams to Morona, and a tug boat would come from Iquitos and pull it further down the Marañon and into the Amazon where it would be sold. There was good money to be made in this business, especially since the patróns generally paid their workers a pittance. Many of them were basically slaves to him. The goods in the stores were expensive compared to the workers salaries, and then they ended up in debt to the patrón so they had to keep working for him. It didn’t help that one of the more popular wares was liquor. We were saddened to see this vicious circle of poverty and exploitation. Fortunately, this system has lessened over the years as people have become more educated.

The patrón in Copal was very excited that we had come. He was preparing for a large celebration of a Catholic holiday and invited us to the party. There was not a church in Copal, but the inhabitants knew of the Catholic holidays, and it was a good opportunity for the whole village to party with plenty of food and alcohol. There were not really any religious aspects to this celebration other than the name. The patrón had sent his workers hunting for many days and showed us a lot of smoked meat from wild boar and many live turtles of both the water and land varieties. They had also prepared many jugs of “Masato”, a drink made from manioc. The boiled manioc is mashed, then chewed, and spit back in the pot. This starts the fermentation process. When it is fresh, it is not fermented yet, and it is used as a drink even for children. However, when it has been stored for several days, it becomes very strong. These jugs had been set aside 3 - 5 days ago and were quite alcoholic by this point. According to the patrón, everything was in place for a great party.

We declined the invitation as politely as we could, but since the party was not to be held until the following evening, we asked him if we could hold a service in his house this evening. He heartily agreed and sent messengers out to the village to spread the news about the meeting. Back in our boat, we had time to eat dinner and prepare for the service before we headed back up to the patrón’s big house. As darkness fell, people arrived for the meeting. To our surprise, 50 - 60 people showed up. Where did they all come from? All we had seen were a few houses! But we soon discovered that many lived further in the jungle next to small lakes or creeks, and their houses could not be seen from the river. It was the first time for most of them to hear the good news of salvation through Jesus Christ. Everyone enjoyed the accordion and the singing, and the children and the younger people soon joined in as they learned the choruses. One of the patrón’s adult sons asked for prayer. We had a good talk with him and prayed with him after most people had gone home. He was the first one on this trip we were able to pray for.

Pincha Cocha

We traveled on, and after a couple of short stops at some houses we arrived in Pincha Cocha and stayed there for a couple of days. This village also had a patrón who remembered me from my earlier visit. He considered himself the patrón of the Chapra tribe. He had a nice house on a hill and many cattle. His workers lived in smaller huts along the river. He had set up a trading station where he sold things like rifles, ammunition, flashlights, batteries, soap, fishing gear, paraffin, matches, fabric, and sewing supplies. The Chapra would come here to trade with wild meat, jaguar pelts (which later was forbidden to be sold), and lumber. Somehow the trading always ended up in the patrón’s favor and after several years, he was quite well off.

We were well received by everyone and were allowed to hold services in the schoolhouse. Most of the inhabitants came to the evening services and listened eagerly. Many requested tracts and Bible portions. Many adults could not read, but their children were learning and would read to them. We spent a couple of nice days in Pincha Cocha and restocked our food supply with fish, bananas, and manioc. We usually had manioc for dinner. It was a good replacement for potatoes that did not thrive in the hot and humid climate of the jungle.

As we went to bed the last night here, we were looking forward to continuing up the river to Shoroya Cocha in the Chapra territory. God's Word continued to be sown, and we prayed it would produce much fruit.

We traveled on, and after a couple of short stops at some houses we arrived in Pincha Cocha and stayed there for a couple of days. This village also had a patrón who remembered me from my earlier visit. He considered himself the patrón of the Chapra tribe. He had a nice house on a hill and many cattle. His workers lived in smaller huts along the river. He had set up a trading station where he sold things like rifles, ammunition, flashlights, batteries, soap, fishing gear, paraffin, matches, fabric, and sewing supplies. The Chapra would come here to trade with wild meat, jaguar pelts (which later was forbidden to be sold), and lumber. Somehow the trading always ended up in the patrón’s favor and after several years, he was quite well off.

We were well received by everyone and were allowed to hold services in the schoolhouse. Most of the inhabitants came to the evening services and listened eagerly. Many requested tracts and Bible portions. Many adults could not read, but their children were learning and would read to them. We spent a couple of nice days in Pincha Cocha and restocked our food supply with fish, bananas, and manioc. We usually had manioc for dinner. It was a good replacement for potatoes that did not thrive in the hot and humid climate of the jungle.

As we went to bed the last night here, we were looking forward to continuing up the river to Shoroya Cocha in the Chapra territory. God's Word continued to be sown, and we prayed it would produce much fruit.