Chapter 21: Exploring the Jungle, Part 4

Visiting the Chapra village and over the mountain with the Wampis tribe

AS TOLD BY JOHN AGERSTEN

Meeting the Chapra Tribe

The river disappeared behind us as we followed the small path into the jungle. The Chapra men kept a good, fast pace, and I had to push myself to keep up with them. It would not be good to be left behind and alone in this jungle! There was a lot of water and mud everywhere, but trunks had been laid over the worst places, basically functioning as 70 to 90 feet bridges. The men crossed these just as quickly as on the dry ground, but I had to go much slower in order to not fall off the slippery trunks. The men would wait for me, but I am sure they were amused by this “gringo” who didn’t have good balancing skills.

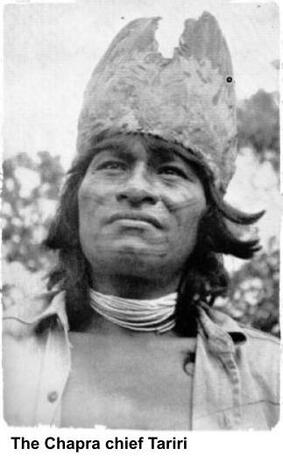

After about 30 minutes, we suddenly came to a hill. It was a steep rise of about 30 feet up to a plateau. Just a few minutes later, we arrived at a manioc field, and looking a little further, I was surprised to see a tin roof among the palms. Closer, I could see it was a pretty, blue, two-story house made of wood. This was totally unexpected, and I was still pondering this when I heard angry, shouting voices. It was a group of 8 to 10 men shouting at each other at full volume, and obviously quarreling. Fear gripped me, and I considered running back down the path toward the river, but the men with me pushed me forward onto the clearing in front of the house. Seeing me had an astonishing effect on the group. They quit their shouting as if by magic, and now there was a heavy silence. More men came out the door, and they had painted faces with red and black patterns. Some of them wore crowns of toucan feathers and bracelets and necklaces with feathers and shells. The men who had brought me said a few words in their language, and a shorter, powerfully built man came toward me and looked at me up and down. He was wearing a very impressive crown. He asked me something in his language, and a younger man translated it into Spanish: “Who are you and what do you want here?” I managed to say that I was a missionary from Norway. I didn’t hold out much hope that he knew what Norway was and thought he might not know the word “missionary” either. His expression didn’t change as he continued to question me through his interpreter: “What kind of missionary are you? We don’t accept just any kind of missionary here!” I was very surprised at this and tried to explain I was a missionary from a pentecostal church, at the same time thinking he wouldn’t know what that was. So I was even more astonished when he said, this time in Spanish; ”Then you are very welcome here!” It was Tariri himself standing in front of me.

The river disappeared behind us as we followed the small path into the jungle. The Chapra men kept a good, fast pace, and I had to push myself to keep up with them. It would not be good to be left behind and alone in this jungle! There was a lot of water and mud everywhere, but trunks had been laid over the worst places, basically functioning as 70 to 90 feet bridges. The men crossed these just as quickly as on the dry ground, but I had to go much slower in order to not fall off the slippery trunks. The men would wait for me, but I am sure they were amused by this “gringo” who didn’t have good balancing skills.

After about 30 minutes, we suddenly came to a hill. It was a steep rise of about 30 feet up to a plateau. Just a few minutes later, we arrived at a manioc field, and looking a little further, I was surprised to see a tin roof among the palms. Closer, I could see it was a pretty, blue, two-story house made of wood. This was totally unexpected, and I was still pondering this when I heard angry, shouting voices. It was a group of 8 to 10 men shouting at each other at full volume, and obviously quarreling. Fear gripped me, and I considered running back down the path toward the river, but the men with me pushed me forward onto the clearing in front of the house. Seeing me had an astonishing effect on the group. They quit their shouting as if by magic, and now there was a heavy silence. More men came out the door, and they had painted faces with red and black patterns. Some of them wore crowns of toucan feathers and bracelets and necklaces with feathers and shells. The men who had brought me said a few words in their language, and a shorter, powerfully built man came toward me and looked at me up and down. He was wearing a very impressive crown. He asked me something in his language, and a younger man translated it into Spanish: “Who are you and what do you want here?” I managed to say that I was a missionary from Norway. I didn’t hold out much hope that he knew what Norway was and thought he might not know the word “missionary” either. His expression didn’t change as he continued to question me through his interpreter: “What kind of missionary are you? We don’t accept just any kind of missionary here!” I was very surprised at this and tried to explain I was a missionary from a pentecostal church, at the same time thinking he wouldn’t know what that was. So I was even more astonished when he said, this time in Spanish; ”Then you are very welcome here!” It was Tariri himself standing in front of me.

I was invited into his house and seated at a table while all the people from outside also came pouring in. Tariri explained that they were discussing a problem. A teacher had been at the Wycliffe missionary base studying. He was now back but had discovered on his return that another man had taken his wife while he was gone. He now wanted her back. They continued the discussion, but not like I was used to where one person spoke at a time. Here they all spoke at the same time and had to be loud in an attempt to be heard. For a while, I thought an actual fight would break out, which would not be good since most of them seemed to be holding a rifle and had cartridge cases slung over their shoulders. However, after about half an hour, it quieted, everyone looked satisfied and left for their own homes. I never did find out what was decided about the young man and his wife.

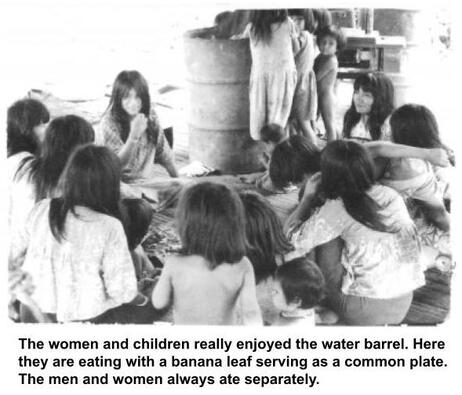

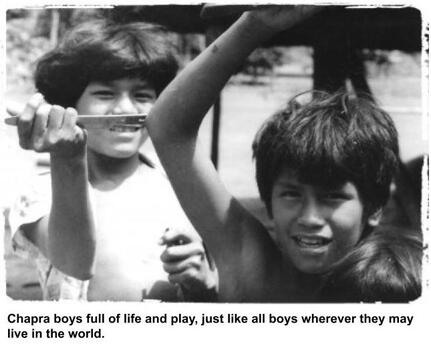

After a while, I was served chicken soup at a large table. I asked Tariri about the house since it was rather unusual in the jungle. The answer was just as surprising as the house itself! It had been built by some carpenters that came from the USA. They were part of the Wycliffe Bible translators. The roof had come from Florida through the same organization. After talking for a while, I was shown to an empty hut consisting of a floor and roof, but no walls. I set up my mosquito netting and blew up my air mattress, which was met with amazement and much interest by the children around me. There were adults close by as well, paying close attention to my every move. I had a large bathroom; the whole jungle was at my disposal. At least they didn’t keep pigs here! I awoke refreshed the next morning to a flock of children surrounding my bed.

After a while, I was served chicken soup at a large table. I asked Tariri about the house since it was rather unusual in the jungle. The answer was just as surprising as the house itself! It had been built by some carpenters that came from the USA. They were part of the Wycliffe Bible translators. The roof had come from Florida through the same organization. After talking for a while, I was shown to an empty hut consisting of a floor and roof, but no walls. I set up my mosquito netting and blew up my air mattress, which was met with amazement and much interest by the children around me. There were adults close by as well, paying close attention to my every move. I had a large bathroom; the whole jungle was at my disposal. At least they didn’t keep pigs here! I awoke refreshed the next morning to a flock of children surrounding my bed.

Tariri and the Wycliffe Bible Translators.

I stayed with Tariri and the Chapra in Shoroya Cocha for a few days, and we became good friends. Tariri had heard the Gospel from two Wycliffe women who had come to their village in the ‘50s. They had built a hut here, lived here, learned their language, and created a written language for them. Now they were in the process of translating the New Testament into their language at the Wycliffe missions base in Yarina Cocha. That base was about 560 miles southeast by air. The missionaries would still come and stay for two-three months at a time once or twice a year. They would also bring young natives from different tribes to their base in Yarina and educate them as teachers or health workers. A few years ago a book had been written about Tariri’s conversion called “Tariri, my Story”. Apparently, it had been a big hit among Christians in the US. Tariri himself had visited the US twice. He told me several times that he wanted his tribe to be educated in the Word of God so that they could live better lives. I had to promise him I would be back to teach them and other Chapra villages. I was told there were more Chapra villages and groups that did not know much about the Gospel. They lived further into the jungle and along small tributaries to Morona. There were also groups that had separated themselves from Tariri and his new faith and lifestyle. Some groups called themselves Kandozi but spoke the same language. They lived further east by the lake Rimachi and along tributaries to the river Pastaza which comes from Ecuador and flows into the Marañon River further east. They traveled on jungle paths between Morona and Pastaza.

On one of my days in Shoroya, a small pontoon plane circled the village. Everyone ran down the path to the river where the plane had landed. It was a plane from the Wycliff base that came with medicines and a few other things for the village. One of the items was a big box containing a lawn mower. The plane left, and all the packages were carried up to the village. The lawnmower box was opened amid much excitement, only to find it was not assembled. It did include an instruction book, but no one dared to try to assemble it. Tariri asked me to try, and after some trial and error, it was finally ready to be started. They had some gasoline, but no oil. As it turned out, the young teacher who had studied in Yarina had a gallon of oil which he graciously offered. It was a tense moment as we started to pull on the starter rope, but after a few tries, the engine came to life. I had to take a picture of a proud Tariri cutting the grass in front of his house.

I stayed with Tariri and the Chapra in Shoroya Cocha for a few days, and we became good friends. Tariri had heard the Gospel from two Wycliffe women who had come to their village in the ‘50s. They had built a hut here, lived here, learned their language, and created a written language for them. Now they were in the process of translating the New Testament into their language at the Wycliffe missions base in Yarina Cocha. That base was about 560 miles southeast by air. The missionaries would still come and stay for two-three months at a time once or twice a year. They would also bring young natives from different tribes to their base in Yarina and educate them as teachers or health workers. A few years ago a book had been written about Tariri’s conversion called “Tariri, my Story”. Apparently, it had been a big hit among Christians in the US. Tariri himself had visited the US twice. He told me several times that he wanted his tribe to be educated in the Word of God so that they could live better lives. I had to promise him I would be back to teach them and other Chapra villages. I was told there were more Chapra villages and groups that did not know much about the Gospel. They lived further into the jungle and along small tributaries to Morona. There were also groups that had separated themselves from Tariri and his new faith and lifestyle. Some groups called themselves Kandozi but spoke the same language. They lived further east by the lake Rimachi and along tributaries to the river Pastaza which comes from Ecuador and flows into the Marañon River further east. They traveled on jungle paths between Morona and Pastaza.

On one of my days in Shoroya, a small pontoon plane circled the village. Everyone ran down the path to the river where the plane had landed. It was a plane from the Wycliff base that came with medicines and a few other things for the village. One of the items was a big box containing a lawn mower. The plane left, and all the packages were carried up to the village. The lawnmower box was opened amid much excitement, only to find it was not assembled. It did include an instruction book, but no one dared to try to assemble it. Tariri asked me to try, and after some trial and error, it was finally ready to be started. They had some gasoline, but no oil. As it turned out, the young teacher who had studied in Yarina had a gallon of oil which he graciously offered. It was a tense moment as we started to pull on the starter rope, but after a few tries, the engine came to life. I had to take a picture of a proud Tariri cutting the grass in front of his house.

Leaving Shoroya and continuing up the Morona

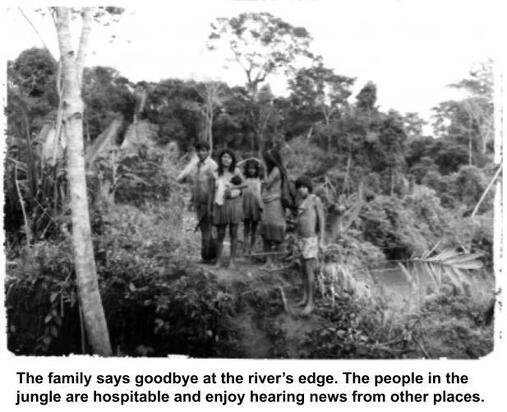

I really enjoyed my stay in the village, but I had to move on. After three days in Shoroya, I walked the path back to the river and sat down to wait for any boats passing by. I waited most of the day, but finally, a merchant boat came by that was traveling upstream. The boat docked when I waved, and I was told I was welcome to go with them. We left immediately, as this merchant didn’t seem to want to deal with the Chapra either.

That evening we spent the night in a house with a mestizo family. The man was a “patron” in the area. They seemed to be having a party with a lot of alcohol involved, so I went to bed quite early at my designated place. The next morning, I was told there is a path over the mountain that goes west to the river Santiago on the other side. From there I could hitch a ride on a boat down the Santiago river to the Marañon and get home without having to go back up the rapids at Pongo de Manseriche. As we were leaving, they said to get off the merchant boat at a house a few hours further up the Morona. That is where the path over the mountain started, according to my host.

After a few hours, I was set ashore by a palm hut on the west side of the river, and the merchant continued his journey immediately. As I approached the house, I realized no one had lived here for a while. There were holes in the roof and no signs of anything that might belong to the owners. I was getting worried as I walked around shouting, and only insects and frogs answered me. I hid my luggage and started looking for a path. I found several and decided to follow the largest one. It seemed more recently used. About half an hour’s walk into the jungle, I was about to give up and return to the river, but then I heard a rooster crow. Surely where there were roosters, there would be people! I walked a little further and came to a clearing with a couple of houses by a small river. The only one at home was an elderly woman, and she screamed when she saw me, a white, bearded stranger, coming out of the woods. I could hear the sounds of an ax being used further in, and when the woman screamed, a man came running with an ax and a machete. As soon as the fright was over, he asked me in Spanish who I was and what I wanted. I explained my situation, and I was invited to spend the night with them. He went with me back to the river to retrieve my luggage, and on the way, we met three men from the place I had spent the previous night. They had come to find me when they remembered that the house they had indicated was currently empty. They also wanted to ask me if I could come back to their village and start a school for their children. I explained that it would be difficult, and I certainly couldn’t promise anything.

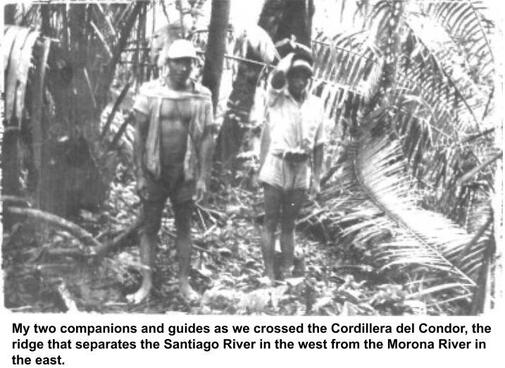

The people living at this place were of the Wampis tribe, with one mestizo man. I was told that there were several small Wampis settlements in this area, but that the majority of the tribe lived on the Santiago river and in the hills between the Morona and the Santiago. They are a large tribe with a language similar to the Awajun. It was decided that evening that two of the Wampis men would go with me over the mountain to the river on the other side. Now they asked me to look in on a sick, young woman with a baby lying under a mosquito net in the family hut. Her whole body was covered in sores, and the baby’s as well. I had never seen anything like it. It looked awful. They asked if I had medicines with me that could help her, but unfortunately, I did not. She was clearly in a lot of pain, and I felt very sad that I could not help. I included the poor mother and her baby in my prayers that night as I lay in my mosquito net. Since I wasn’t staying, I would never know if they recovered.

I really enjoyed my stay in the village, but I had to move on. After three days in Shoroya, I walked the path back to the river and sat down to wait for any boats passing by. I waited most of the day, but finally, a merchant boat came by that was traveling upstream. The boat docked when I waved, and I was told I was welcome to go with them. We left immediately, as this merchant didn’t seem to want to deal with the Chapra either.

That evening we spent the night in a house with a mestizo family. The man was a “patron” in the area. They seemed to be having a party with a lot of alcohol involved, so I went to bed quite early at my designated place. The next morning, I was told there is a path over the mountain that goes west to the river Santiago on the other side. From there I could hitch a ride on a boat down the Santiago river to the Marañon and get home without having to go back up the rapids at Pongo de Manseriche. As we were leaving, they said to get off the merchant boat at a house a few hours further up the Morona. That is where the path over the mountain started, according to my host.

After a few hours, I was set ashore by a palm hut on the west side of the river, and the merchant continued his journey immediately. As I approached the house, I realized no one had lived here for a while. There were holes in the roof and no signs of anything that might belong to the owners. I was getting worried as I walked around shouting, and only insects and frogs answered me. I hid my luggage and started looking for a path. I found several and decided to follow the largest one. It seemed more recently used. About half an hour’s walk into the jungle, I was about to give up and return to the river, but then I heard a rooster crow. Surely where there were roosters, there would be people! I walked a little further and came to a clearing with a couple of houses by a small river. The only one at home was an elderly woman, and she screamed when she saw me, a white, bearded stranger, coming out of the woods. I could hear the sounds of an ax being used further in, and when the woman screamed, a man came running with an ax and a machete. As soon as the fright was over, he asked me in Spanish who I was and what I wanted. I explained my situation, and I was invited to spend the night with them. He went with me back to the river to retrieve my luggage, and on the way, we met three men from the place I had spent the previous night. They had come to find me when they remembered that the house they had indicated was currently empty. They also wanted to ask me if I could come back to their village and start a school for their children. I explained that it would be difficult, and I certainly couldn’t promise anything.

The people living at this place were of the Wampis tribe, with one mestizo man. I was told that there were several small Wampis settlements in this area, but that the majority of the tribe lived on the Santiago river and in the hills between the Morona and the Santiago. They are a large tribe with a language similar to the Awajun. It was decided that evening that two of the Wampis men would go with me over the mountain to the river on the other side. Now they asked me to look in on a sick, young woman with a baby lying under a mosquito net in the family hut. Her whole body was covered in sores, and the baby’s as well. I had never seen anything like it. It looked awful. They asked if I had medicines with me that could help her, but unfortunately, I did not. She was clearly in a lot of pain, and I felt very sad that I could not help. I included the poor mother and her baby in my prayers that night as I lay in my mosquito net. Since I wasn’t staying, I would never know if they recovered.

Over the mountain

We started before six the next morning, just as it was starting to get light. We rowed in a small canoe up the small tributary river for about three hours. It was beautiful to see the jungle hanging over the water on both sides and to hear the birds and animal sounds, while the morning fog lifted as the sun grew higher in the sky. Gliding quietly on the water in a small canoe was a totally different experience than traveling in a noisy motor boat that scared away both birds and beasts.

We pulled the canoe up on land where they said the path started, I couldn’t even see it at first, but on closer inspection, I could see a place where it looked like someone may have possibly walked some time in the past. This was to be my first lesson in finding my way in the jungle. I noticed that the man in the front would break the tips of branches at about shoulder height. He would bend the tip in the direction we were going and leave it hanging like that. When I asked him why he was doing that, he told me to look behind me. The leaves on the underside of the broken branch were lighter and created clear signs of the path. To go back, they would easily follow these markers. With time, these leaves would turn brown and would be even easier to see.

We kept up a good pace, although at times it was so steep that we had to crawl and drag ourselves up by roots and vines. After about eight hours with only a couple of breaks to eat a banana and drink some sweet “masato”, it started to get dark and we came to a “tambo”. It was a small hut with a palm roof, but no walls. We would spend the night here. Dinner was a sparse affair, as all they had were a few bananas. We found a few ears of corn in the hut, which they roasted over the fire, and I shared a can of tuna with them. A few planks would serve as a bed, but just as I was about to fall asleep, I heard a strange growling sound. I sat up and saw that my companions were already up. One had a rifle and the other a machete. I asked quietly if they knew what it was. “Un Tigre” was the answer, which is what the natives call the jaguar. I have to admit I was afraid. The hut had no walls and it was scary to think that there was a jaguar out there that had picked up our scent. One of the men threw more wood on the fire so it flared up again. We heard it growl a couple of more times, but then it got quiet. We took turns keeping watch for the rest of the night.

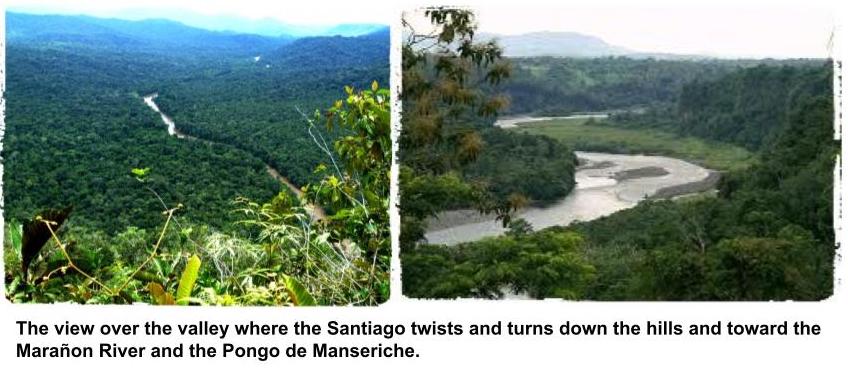

The next morning, after walking for about an hour, we found ourselves at the top of the ridge. From here we had a beautiful view of the valley on the other side and the Santiago river. Now we were truly in the Wampis territory. Around noon, we arrived at a village with a school. The teacher had just returned by hitching a ride on a boat. The boat owner was just eating lunch before going downriver again, and he agreed to let me go with him. Again, I had to rejoice as it seemed that the Lord had arranged for my travel ahead of time! They served me a delicious meal of venison, boiled green bananas, and manioc. It tasted especially good after walking over the mountain.

The trip down the river went smoothly. I was very tired and happy to not be walking. We were allowed to spend the night at the Oxidental oil company base, and I was received very warmly by the Americans there who were extremely curious about where I came from and what I was doing there. It was wonderful to be able to take a warm shower, have a good meal, and then crawl into bed between clean sheets.

From here I hitched a ride with a merchant up the Marañon river back to Chiriaco where I had started my jungle trip three weeks earlier. Then I rode four hours on the back of a truck back to Bagua Chica. It was so wonderful to be back home after such a long trip under primitive conditions and with no possibility to contact my family. Gro prepared a feast, and we were all so happy to be together again and to know that God had protected both me and my family.

We started before six the next morning, just as it was starting to get light. We rowed in a small canoe up the small tributary river for about three hours. It was beautiful to see the jungle hanging over the water on both sides and to hear the birds and animal sounds, while the morning fog lifted as the sun grew higher in the sky. Gliding quietly on the water in a small canoe was a totally different experience than traveling in a noisy motor boat that scared away both birds and beasts.

We pulled the canoe up on land where they said the path started, I couldn’t even see it at first, but on closer inspection, I could see a place where it looked like someone may have possibly walked some time in the past. This was to be my first lesson in finding my way in the jungle. I noticed that the man in the front would break the tips of branches at about shoulder height. He would bend the tip in the direction we were going and leave it hanging like that. When I asked him why he was doing that, he told me to look behind me. The leaves on the underside of the broken branch were lighter and created clear signs of the path. To go back, they would easily follow these markers. With time, these leaves would turn brown and would be even easier to see.

We kept up a good pace, although at times it was so steep that we had to crawl and drag ourselves up by roots and vines. After about eight hours with only a couple of breaks to eat a banana and drink some sweet “masato”, it started to get dark and we came to a “tambo”. It was a small hut with a palm roof, but no walls. We would spend the night here. Dinner was a sparse affair, as all they had were a few bananas. We found a few ears of corn in the hut, which they roasted over the fire, and I shared a can of tuna with them. A few planks would serve as a bed, but just as I was about to fall asleep, I heard a strange growling sound. I sat up and saw that my companions were already up. One had a rifle and the other a machete. I asked quietly if they knew what it was. “Un Tigre” was the answer, which is what the natives call the jaguar. I have to admit I was afraid. The hut had no walls and it was scary to think that there was a jaguar out there that had picked up our scent. One of the men threw more wood on the fire so it flared up again. We heard it growl a couple of more times, but then it got quiet. We took turns keeping watch for the rest of the night.

The next morning, after walking for about an hour, we found ourselves at the top of the ridge. From here we had a beautiful view of the valley on the other side and the Santiago river. Now we were truly in the Wampis territory. Around noon, we arrived at a village with a school. The teacher had just returned by hitching a ride on a boat. The boat owner was just eating lunch before going downriver again, and he agreed to let me go with him. Again, I had to rejoice as it seemed that the Lord had arranged for my travel ahead of time! They served me a delicious meal of venison, boiled green bananas, and manioc. It tasted especially good after walking over the mountain.

The trip down the river went smoothly. I was very tired and happy to not be walking. We were allowed to spend the night at the Oxidental oil company base, and I was received very warmly by the Americans there who were extremely curious about where I came from and what I was doing there. It was wonderful to be able to take a warm shower, have a good meal, and then crawl into bed between clean sheets.

From here I hitched a ride with a merchant up the Marañon river back to Chiriaco where I had started my jungle trip three weeks earlier. Then I rode four hours on the back of a truck back to Bagua Chica. It was so wonderful to be back home after such a long trip under primitive conditions and with no possibility to contact my family. Gro prepared a feast, and we were all so happy to be together again and to know that God had protected both me and my family.