Chapter 25: The First Trip in El Sembrador

AS TOLD BY JOHN AGERSTEN

AS TOLD BY JOHN AGERSTEN

In a letter home to Norway, I write about the day we were finally able to take El Sembrador on its first journey:

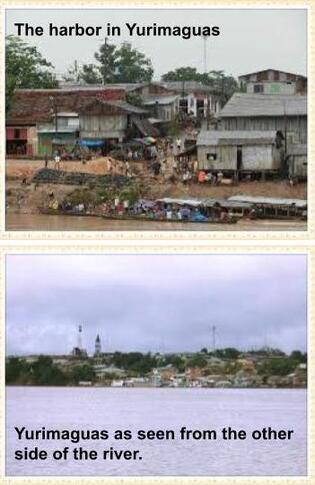

“ After checking for mail one last time at the post office, and sending a letter to Gro, we finally left the harbor and headed toward Borja. It feels great to finally head back to my family. A milestone has been reached! Something new has begun!”

The boat could be steered by the wheel in the front wheelhouse, but starting the motor and operating the throttle had to be done from the back on the outboard motor itself. Alejandro was a skilled motorist, so we took turns with the motor in the back and the steering. He also taught me a lot about the basics of navigating the rivers. The Huallaga river was about 300 feet wide in most places, and the landscape was flat, so the current was not very strong except in the river’s many bends; there it would pick up speed and you had to pay close attention. Trees and logs that had fallen into the river were a constant risk. It was best to stay in the middle of the river when going downstream, but when traveling upriver, it was better to stay close to the inner side of the bends where the current was calmer. Alejandro also taught me how to read the whirlpools caused by the current and the waves to determine where the river was shallow or where logs might be hiding under the surface.

“ After checking for mail one last time at the post office, and sending a letter to Gro, we finally left the harbor and headed toward Borja. It feels great to finally head back to my family. A milestone has been reached! Something new has begun!”

The boat could be steered by the wheel in the front wheelhouse, but starting the motor and operating the throttle had to be done from the back on the outboard motor itself. Alejandro was a skilled motorist, so we took turns with the motor in the back and the steering. He also taught me a lot about the basics of navigating the rivers. The Huallaga river was about 300 feet wide in most places, and the landscape was flat, so the current was not very strong except in the river’s many bends; there it would pick up speed and you had to pay close attention. Trees and logs that had fallen into the river were a constant risk. It was best to stay in the middle of the river when going downstream, but when traveling upriver, it was better to stay close to the inner side of the bends where the current was calmer. Alejandro also taught me how to read the whirlpools caused by the current and the waves to determine where the river was shallow or where logs might be hiding under the surface.

The first day went well, and that afternoon we reached the spot where the Huallaga river joins the Marañon. We had passed many small villages and also the bigger village of Lagunas. An older American missionary couple lived and ministered there and in the area around the village. The rivers Marañon and Ucayali are considered the major tributaries of the Amazon river. They flow together about two days downriver from the mouth of Huallaga. Marañon seemed huge to me as we drove onto it. A beautiful landscape opened up with many islands of different sizes that divided the river into channels, some more than 300 feet wide. My first reaction was to wonder how we would know where to go. We made progress up the river, but we did have to turn around a few times like when we chose the wrong channel which turned out to be a small tributary or one that was blocked by a sandbank. We continued up the Marañon toward the west for a while and spent the night in a small village. I had slept in a hammock for several weeks in Yurimaguas which was hard on my back since I was not used to it. So as we tied up the boat, and settled in for the night, it felt good to stretch out even if it was just on a thin foam mattress.

Traveling up the Marañon to Borja

There were long distances between the villages here. The landscape is flat, and people generally look for higher places to avoid the many floods during the rainy season. We passed some banana and manioc plots, and a few corn and rice plots along the riverbank. But for the most part, the jungle was like an impenetrable wall right up to the river. We could see trees at least 150 feet high covered in vines, and plenty of smaller trees and bushes growing underneath.

We passed the mouth of the river Pastaza that comes out on the north side of the Marañon. I had heard that both mestizos and tribal people lived along that river and some of its smaller tributaries. This tribe belonged to the same group as the Shapra in Morona, but they call themselves Candoshi. We could see a small village at the mouth of the river.

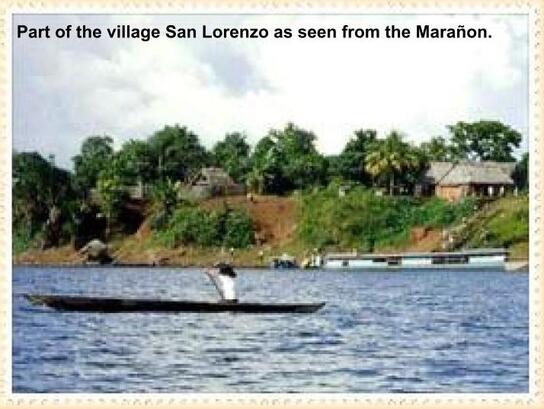

On the third day, we arrived at San Lorenzo, a village founded by Catholic priests and monks from Spain in 1670. The Catholic church ran a school and a clinic here. The church was staffed by a Spanish priest, and Spanish nuns worked at the school and clinic. The Catholic mission considered themselves the owners of the village and decided who could live there. Usually, there was no problem for anyone to move in, but they did not want a Protestant mission established here. This changed after a few years, and we were able to hold services first in homes, and then later we were able to build a church there as well. The village was the largest in the area, and it is situated on a hill that stretches far in from the riverbank. The population here was primarily mestizos.

We left San Lorenzo and continued our travels upriver. Here the Marañon was no longer as wide. We passed the mouth of a smaller tributary, the Cauapanas river. From there it was not far to the military base Barranca. All traffic on the river must stop here regardless of size. We had to register and pass control. Most likely foreigners did not stop by very often, and I was invited to a good dinner with the commander of the base. He was very friendly, and also very curious about what I was doing in this part of the world.

We continued from there and passed several small villages on both sides of the river and another tributary emptying into the Marañon from the south. It was the Potro river which was inhabited mainly by the Awajun tribe. This tribe also lived along the upper Marañon and the Cauapanas river. A few hours later we passed the mouth of the Morona river. It was interesting to see its black, clear water mixing with the muddy Marañon. During the afternoon of the fourth day, the river started to change from a pretty calm and slow current to faster and turbulent waters that created waves and whirlpools in places over rocky sandbanks. In the distance, we could now see the eastern part of the Andes mountain range rising up as a green wall over the forest. We passed the mouth of yet another small tributary, the Apaga.

There were long distances between the villages here. The landscape is flat, and people generally look for higher places to avoid the many floods during the rainy season. We passed some banana and manioc plots, and a few corn and rice plots along the riverbank. But for the most part, the jungle was like an impenetrable wall right up to the river. We could see trees at least 150 feet high covered in vines, and plenty of smaller trees and bushes growing underneath.

We passed the mouth of the river Pastaza that comes out on the north side of the Marañon. I had heard that both mestizos and tribal people lived along that river and some of its smaller tributaries. This tribe belonged to the same group as the Shapra in Morona, but they call themselves Candoshi. We could see a small village at the mouth of the river.

On the third day, we arrived at San Lorenzo, a village founded by Catholic priests and monks from Spain in 1670. The Catholic church ran a school and a clinic here. The church was staffed by a Spanish priest, and Spanish nuns worked at the school and clinic. The Catholic mission considered themselves the owners of the village and decided who could live there. Usually, there was no problem for anyone to move in, but they did not want a Protestant mission established here. This changed after a few years, and we were able to hold services first in homes, and then later we were able to build a church there as well. The village was the largest in the area, and it is situated on a hill that stretches far in from the riverbank. The population here was primarily mestizos.

We left San Lorenzo and continued our travels upriver. Here the Marañon was no longer as wide. We passed the mouth of a smaller tributary, the Cauapanas river. From there it was not far to the military base Barranca. All traffic on the river must stop here regardless of size. We had to register and pass control. Most likely foreigners did not stop by very often, and I was invited to a good dinner with the commander of the base. He was very friendly, and also very curious about what I was doing in this part of the world.

We continued from there and passed several small villages on both sides of the river and another tributary emptying into the Marañon from the south. It was the Potro river which was inhabited mainly by the Awajun tribe. This tribe also lived along the upper Marañon and the Cauapanas river. A few hours later we passed the mouth of the Morona river. It was interesting to see its black, clear water mixing with the muddy Marañon. During the afternoon of the fourth day, the river started to change from a pretty calm and slow current to faster and turbulent waters that created waves and whirlpools in places over rocky sandbanks. In the distance, we could now see the eastern part of the Andes mountain range rising up as a green wall over the forest. We passed the mouth of yet another small tributary, the Apaga.

The boat breaks loose from its mooring.

Toward the end of that day, we struggled to get by a logjam stuck on the tip of an island. The current was beating against the logs and splashing into the air. It created a lot of noise along with the sound of the current dragging small rocks and gravel across the rocky river bottom. We finally got past that and moored by a house on another island a little further upriver. During the night I woke up feeling like something was moving. When I looked out the window, I could see that we were headed quickly downriver with the current! Alejandro woke up as well and ran to start the engine with the start rope. We could hear we were nearing the logjam. Just a few feet away from it the engine finally came to life and we drove slowly upriver and out of the strong current. Fortunately, there was a partial moon so we could see around us. Back at the island, we tied the boat to a tree. The pole we had used the first time, had come loose. I was very shaken and scared and slept little the rest of the night. I was picturing the boat crashing into and being crushed by the river against the logjam. I actually had nightmares about this for a long time. There were times I would sit up in bed and yell: “The boat is loose!”

That last day's journey to Borja was long and a little nerve-wracking. The river was narrower and faster as we were getting closer to the mountains and the Pongo de Manseriche rapids. Usually, we could find a strip closer to the bank where the current was calmer. Finally, we could see the first houses in Borja at the bend of the river. I knew Borja from my travels earlier that year.

This was the end of this journey for El Sembrador. It would be too risky to try to take it up the rapids. A man I had met and gotten to know on my first visit here promised he would keep an eye on the boat while I went to get Gro and the children and all our things. By now I was aware of how quickly the river could rise and fall, especially here this close to the mountains and where the river was so narrow. But for an agreed-upon fee, the man would move the mooring according to the level of the river.

Toward the end of that day, we struggled to get by a logjam stuck on the tip of an island. The current was beating against the logs and splashing into the air. It created a lot of noise along with the sound of the current dragging small rocks and gravel across the rocky river bottom. We finally got past that and moored by a house on another island a little further upriver. During the night I woke up feeling like something was moving. When I looked out the window, I could see that we were headed quickly downriver with the current! Alejandro woke up as well and ran to start the engine with the start rope. We could hear we were nearing the logjam. Just a few feet away from it the engine finally came to life and we drove slowly upriver and out of the strong current. Fortunately, there was a partial moon so we could see around us. Back at the island, we tied the boat to a tree. The pole we had used the first time, had come loose. I was very shaken and scared and slept little the rest of the night. I was picturing the boat crashing into and being crushed by the river against the logjam. I actually had nightmares about this for a long time. There were times I would sit up in bed and yell: “The boat is loose!”

That last day's journey to Borja was long and a little nerve-wracking. The river was narrower and faster as we were getting closer to the mountains and the Pongo de Manseriche rapids. Usually, we could find a strip closer to the bank where the current was calmer. Finally, we could see the first houses in Borja at the bend of the river. I knew Borja from my travels earlier that year.

This was the end of this journey for El Sembrador. It would be too risky to try to take it up the rapids. A man I had met and gotten to know on my first visit here promised he would keep an eye on the boat while I went to get Gro and the children and all our things. By now I was aware of how quickly the river could rise and fall, especially here this close to the mountains and where the river was so narrow. But for an agreed-upon fee, the man would move the mooring according to the level of the river.

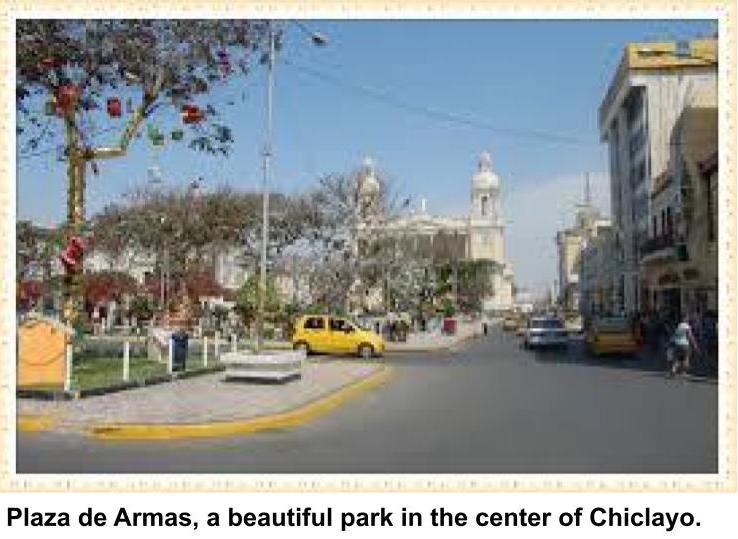

Borja to Chiclayo

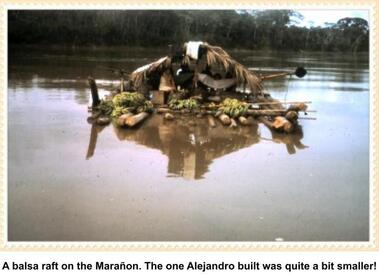

Alejandro and I parted ways in Borja. He was returning to Yurimaguas, and I would catch a ride further upriver, past the rapids to Chiriaco. From there I would go by truck to Bagua. Alejandro built himself a balsa raft, loaded up his little bag, some provisions, an oar, and some bamboo poles, and headed downriver. He was hoping to catch a ride on a boat further down. Later I found out that it had taken him a long time to get home.

I had to wait a couple of days before a boat that was headed further up the river. arrived in Borja. It belonged to a businessman that had been selling his wares downriver. He had a long open wooden boat with an old outboard motor, but the water levels in the river were low, so we had no problem making it up the Manseriche rapids. We arrived in Chiriaco on the third day and I was grateful to see that there was already a truck there headed to Bagua. I climbed onto the back of the truck and arrived in Bagua in about four to five hours.

It was already late by that time and I was tired, so I just went straight to bed. The next morning I called Gro who was still in Lima. The Lindgrens did not have a phone at their house at this time, but I was able to reach someone in the Seaman Church who drove over to give her the message. Gro and the children took the night bus that same evening to Chiclayo. I took a bus from Bagua later that same day. I was excited as I waited for Gro and the children at the bus stop the next morning. It was now October 8th, and a little more than seven weeks had passed since we had said farewell in this same spot. It was almost unbelievable that we were about to see each other again after all that time. But I was grateful to God for everything I had experienced during this time, and that both I and my family had been under God’s protection.

Alejandro and I parted ways in Borja. He was returning to Yurimaguas, and I would catch a ride further upriver, past the rapids to Chiriaco. From there I would go by truck to Bagua. Alejandro built himself a balsa raft, loaded up his little bag, some provisions, an oar, and some bamboo poles, and headed downriver. He was hoping to catch a ride on a boat further down. Later I found out that it had taken him a long time to get home.

I had to wait a couple of days before a boat that was headed further up the river. arrived in Borja. It belonged to a businessman that had been selling his wares downriver. He had a long open wooden boat with an old outboard motor, but the water levels in the river were low, so we had no problem making it up the Manseriche rapids. We arrived in Chiriaco on the third day and I was grateful to see that there was already a truck there headed to Bagua. I climbed onto the back of the truck and arrived in Bagua in about four to five hours.

It was already late by that time and I was tired, so I just went straight to bed. The next morning I called Gro who was still in Lima. The Lindgrens did not have a phone at their house at this time, but I was able to reach someone in the Seaman Church who drove over to give her the message. Gro and the children took the night bus that same evening to Chiclayo. I took a bus from Bagua later that same day. I was excited as I waited for Gro and the children at the bus stop the next morning. It was now October 8th, and a little more than seven weeks had passed since we had said farewell in this same spot. It was almost unbelievable that we were about to see each other again after all that time. But I was grateful to God for everything I had experienced during this time, and that both I and my family had been under God’s protection.